There have been hundreds of them, with tens of thousands of engagements and hundreds of thousands of views. In early November, MIT Technology Review still found dozens of duplicate fake live videos from that period. A pair of duplicates with over 200,000 and 160,000 views, respectively, announced in Burmese: “I’m the only one broadcasting live in real time from across the country.” Facebook deleted some of them after we alerted them, but dozens more as well as that Pages they were posted on still exist. Osborne said the company is aware of the problem and has significantly reduced these fake lives and their spread over the past year.

Ironically, Rio believes the videos likely came from footage of the crisis uploaded to YouTube as evidence of human rights. So the scenes are actually from Myanmar – but they were all posted from Vietnam and Cambodia.

In the past six months, Rio has tracked and identified several side clusters from Vietnam and Cambodia. Many used fake live videos to quickly build their following and get viewers to join Facebook groups disguised as pro-democratic communities. Rio now fears that Facebook’s latest introduction of in-stream ads in live video will further encourage clickbait actors to fake them. An 18-page Cambodian cluster began posting highly damaging political misinformation, reaching a total of 16 million engagements and an audience of 1.6 million in four months. Facebook deleted all 18 pages in March, but new clusters continue to emerge while others persist.

As far as Rio knows, these Vietnamese and Cambodian actors don’t speak Burmese. You probably don’t understand Burmese culture or the country’s politics. The bottom line is that you don’t have to. Not if they steal their content.

Rio has since formed several Cambodian private Facebook and Telegram groups (one of over 3,000 people) where they share tools and tips on the best money-making strategies. MIT Technology Review reviewed the documents, images, and videos it had collected and hired a Khmer translator to interpret a tutorial video that walks viewers step-by-step through a clickbait workflow.

The materials show how the Cambodian operators are collecting research on the top performing content in each country and plagiarizing it for their clickbait websites. A Google Drive folder shared within the community contains two dozen spreadsheets with links to the most popular Facebook groups in 20 countries, including the US, UK, Australia, India, France, Germany, Mexico, and Brazil.

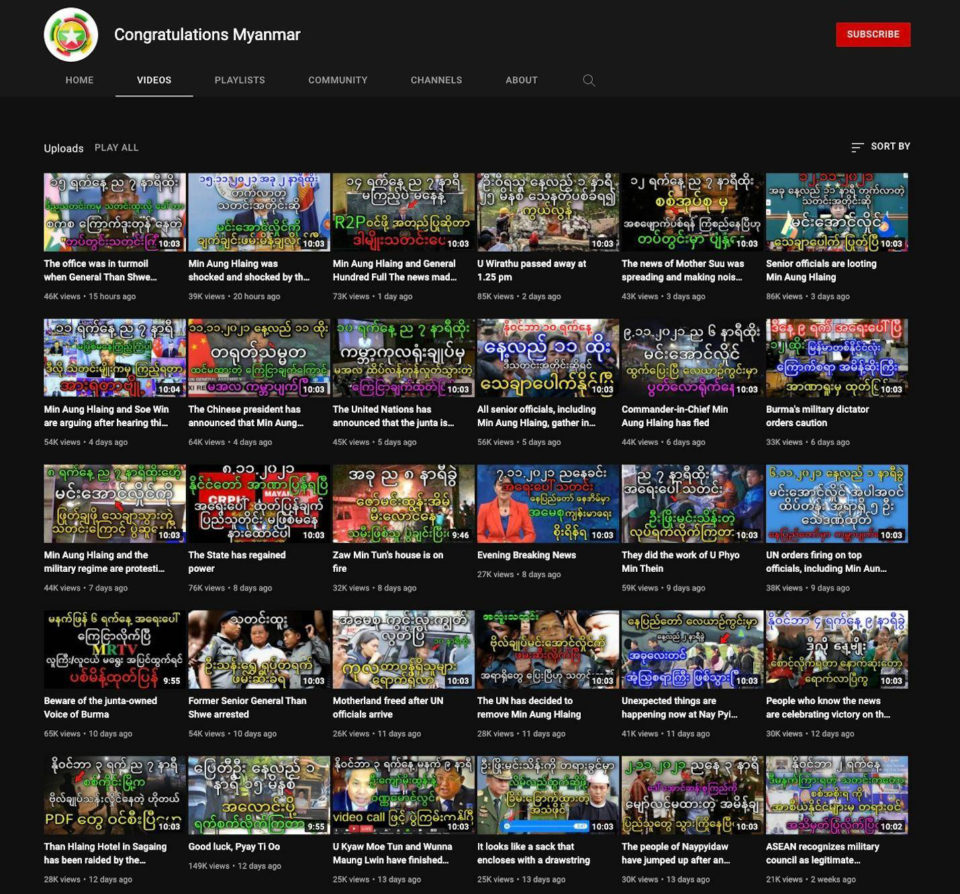

The tutorial video also shows how to find the most viral YouTube videos in different languages and use an automated tool to turn each one into an article for their website. For example, we found 29 YouTube channels spreading political misinformation about the current political situation in Myanmar, which was converted into clickbait articles and passed on to new audiences on Facebook.

One of the YouTube channels spreading political misinformation in Myanmar. Google eventually took it down.

After bringing the channels to our attention, YouTube fired everyone for violating community guidelines, including seven that it found were part of coordinated lobbying related to Myanmar. Choi noted that YouTube had previously also stopped serving nearly 2,000 videos on these channels. “We continue to actively monitor our platforms to prevent bad actors from exploiting our network for profit,” she said.

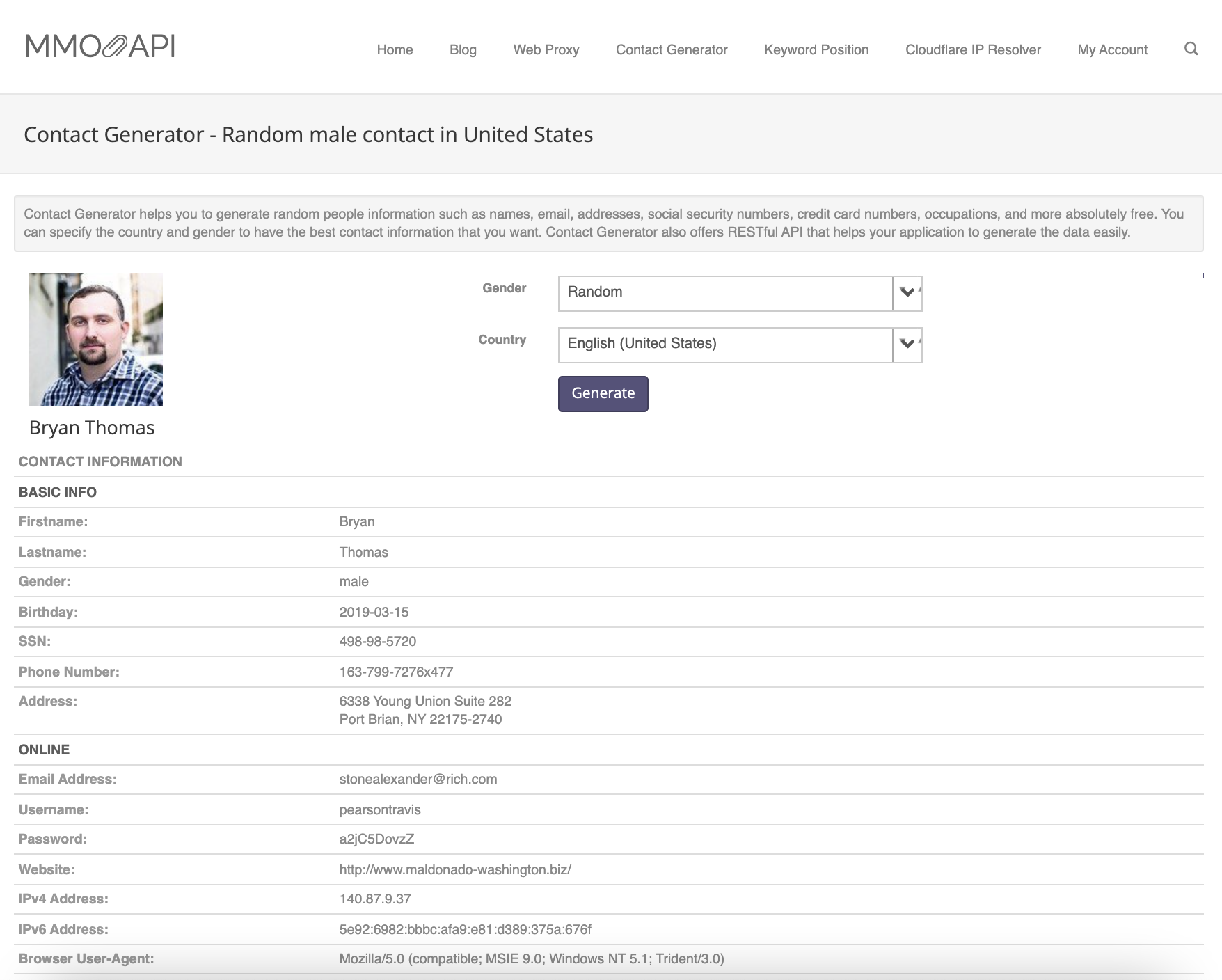

Then there are other tools including one that can be used to display recorded videos as fake Facebook Live videos. Another tool randomly generates profile details for US men, including picture, name, birthday, social security number, phone number, and address, so another tool can use some of that information to create fake Facebook accounts on a massive scale.

It’s so easy now that a lot of Cambodian actors go solo. Rio calls them micro-entrepreneurs. In the most extreme scenario, she has seen individuals manage up to 11,000 Facebook accounts alone.

Successful micro-entrepreneurs also train others to do this work in their community. “It’s getting worse,” she says. “Any joe in the world could affect your information environment without you realizing it.”